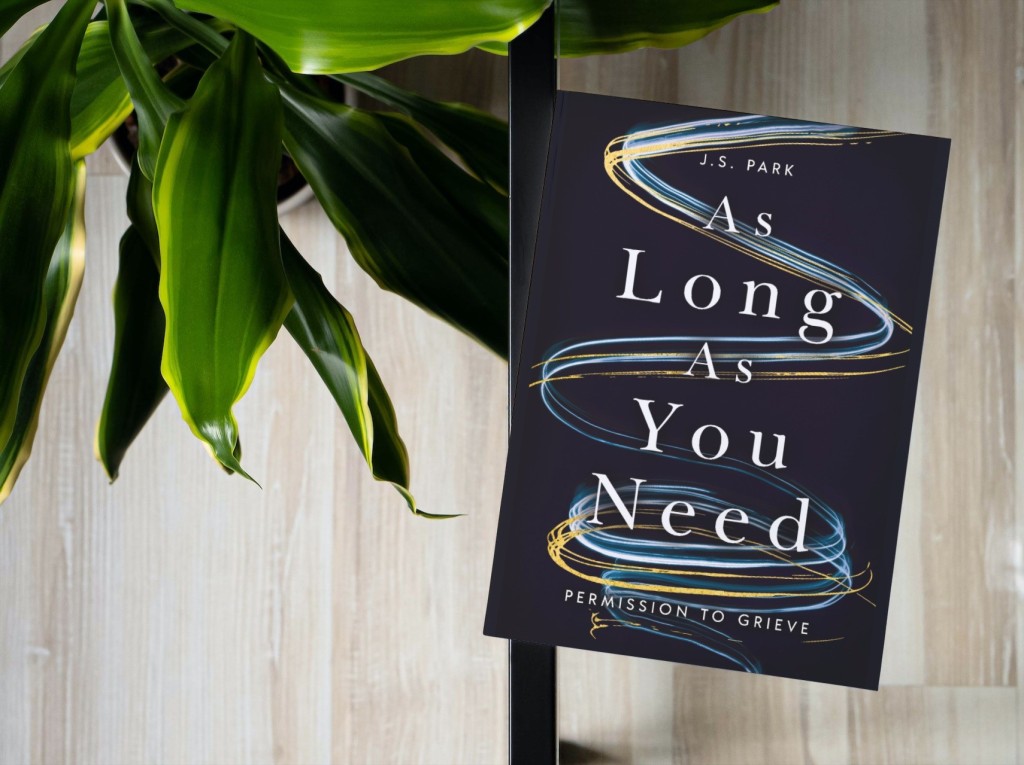

Book title and cover reveal:

• As Long As You Need: Permission to Grieve •

You can now preorder ![]()

•

My book releases on April 16th, 2024.

It’s about grief.

I talk about my hospital chaplain work and multiple dimensions of grief, such as loss of:

/ dreams / mental health / autonomy / community / self-worth after abuse /

I dismantle myths about grief,

share stories from the hospital,

and share what I learned and unlearned from sitting with hundreds of patients.

And it is partially a memoir of my own grief: the death of my friend John, witnessing my wife survive PPD, witnessing the hardest losses on the frontlines, the loss of my faith (and coming back to it, sort of), and confronting my own history of trauma through EMDR. ![]()

•

Second to last photo is my co-author. I always had an open door policy when I was writing. Any time she dropped in, I paused and spent time with her. She’d watch me write or ask me to read it to her or just vibe to the lo-fi. She now calls lo-fi “daddy’s writing music.”

•

Last photo is me after recording some of the audiobook. I didn’t get to narrate my last one (I was told I failed the audition). My new publisher assured me from the start that I’d get to record for this one. Very glad and grateful and honored to be reading my book for you. ![]()

•

This book could not have been written without you. Online family. Your kindness, comments, messages, stories, and feedback were my strength as I took on this emotionally challenging work.

I’ll be doing a few readings randomly in April and May. Would love to meet you. ![]()

•

A special thank you to Faith M Karimi, CNN digital senior writer, for writing the article about me and my work. I got a lot of interest in a book after the article. From phone calls at the hospital to hundreds of messages, I heard from so many sharing their grief stories. I’m reminded that even when it seems like grief is a scary topic, many of us really do want to talk about loss, death, and dying. In this very tough space, I hope to meet you there.

— J.S.