Disclaimer: Angry and disagreeable post to follow.

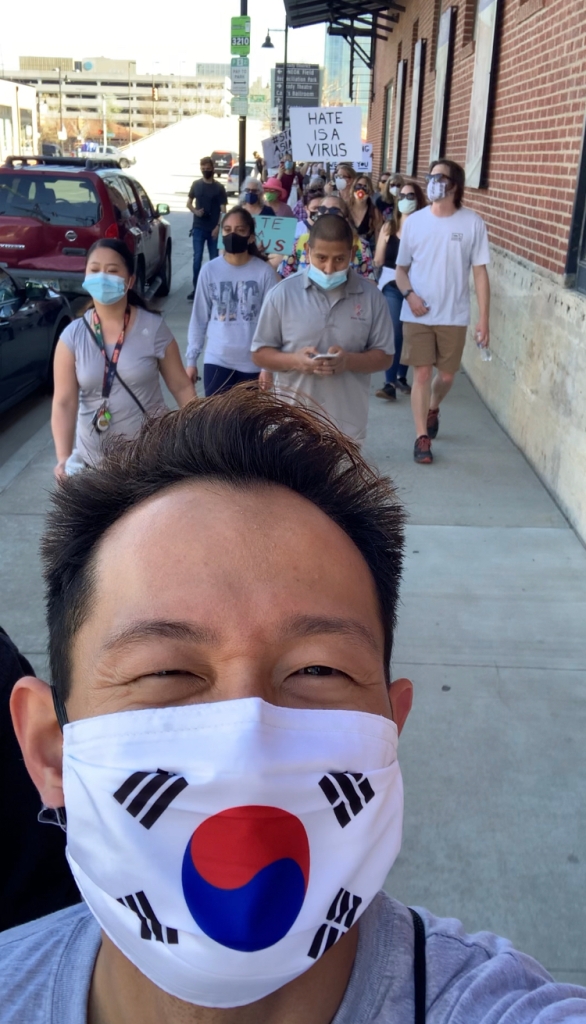

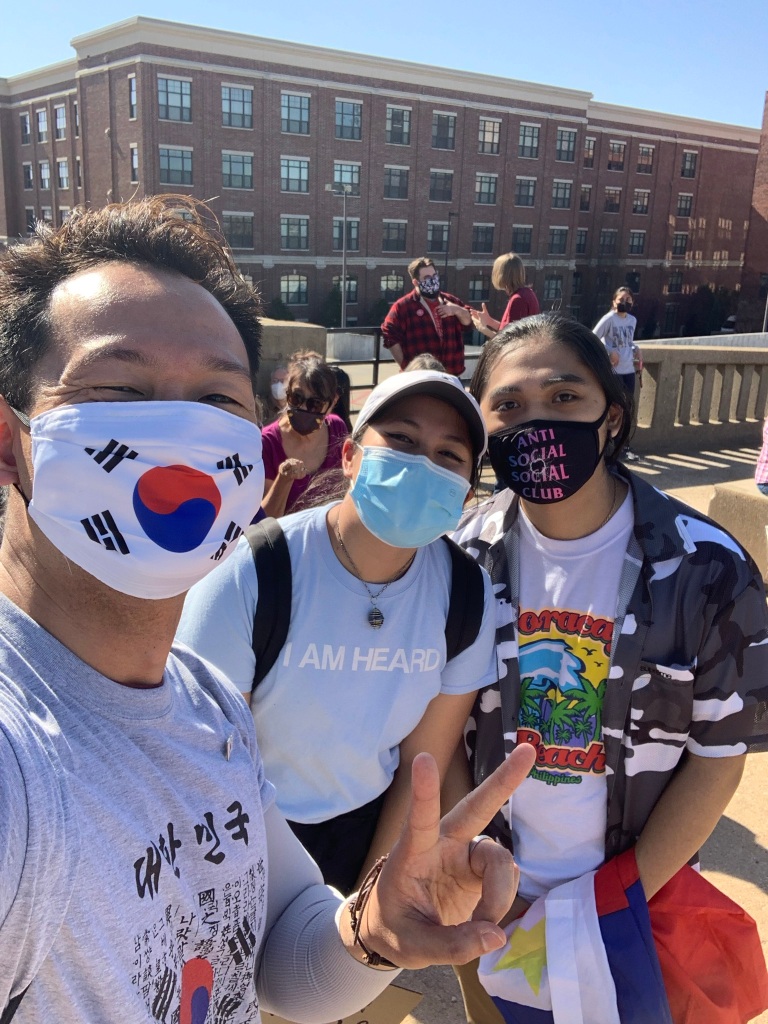

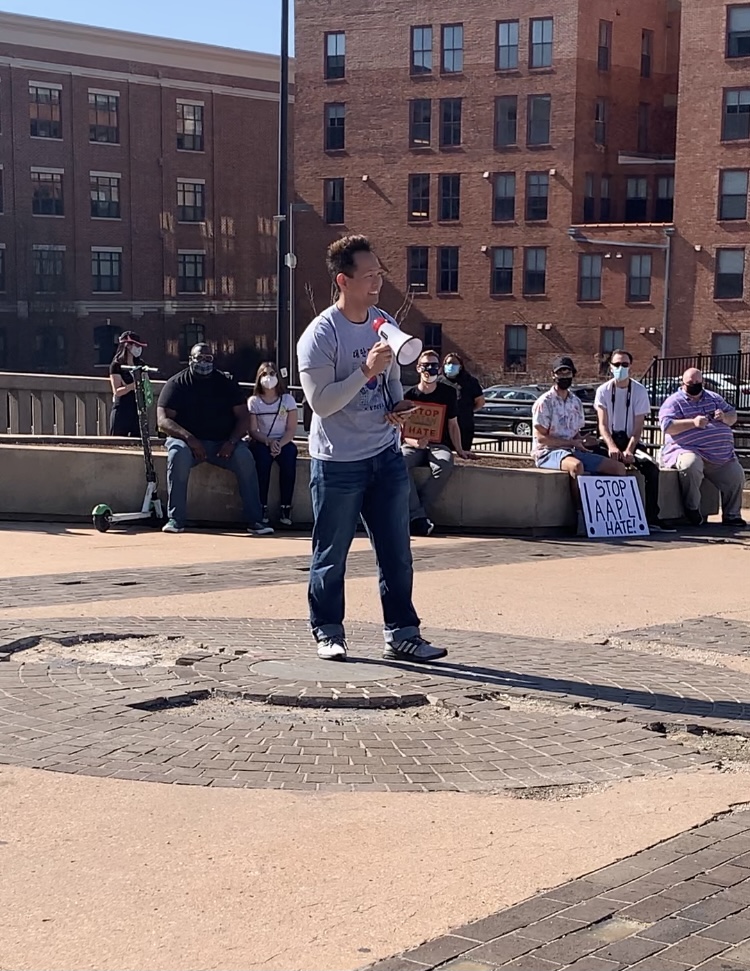

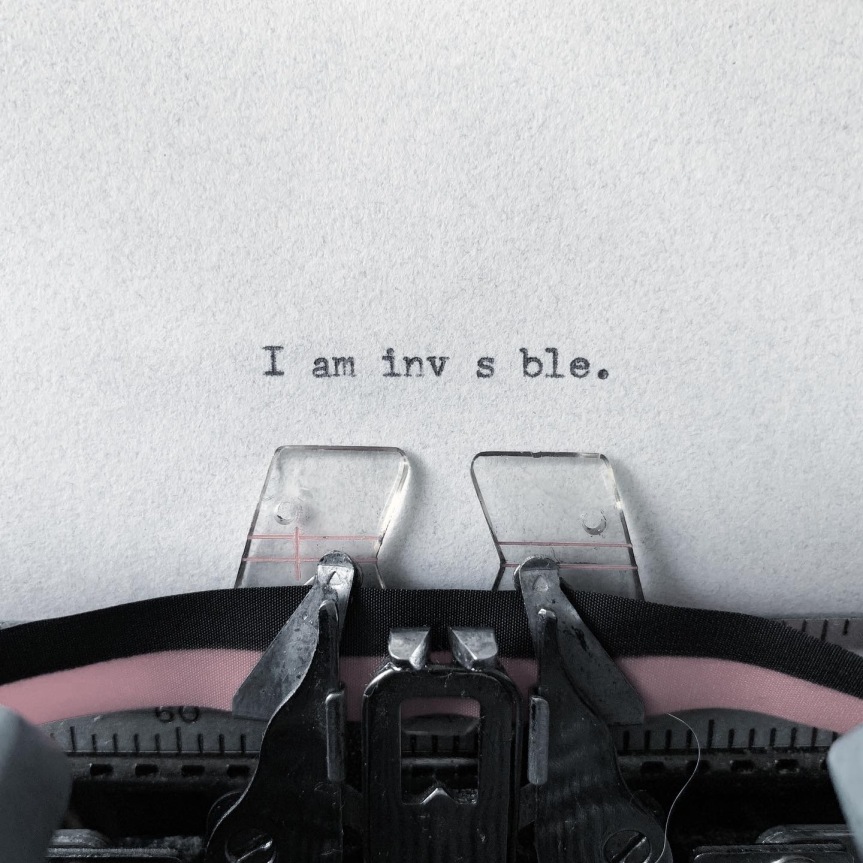

I’m still not over the American church of 2020 withholding comfort for pandemic anxiety, compassionate wisdom for masks and vaccines, and solidarity with POC—

but instead yelling election fraud and “my freedom.”

The church could’ve ended the pandemic in a summer and cut hate crimes by half.

Every Sunday of 2020, I was overwhelmed and hoped for a word of strength and wisdom. Instead the pulpit told me Black lives didn’t matter, masks were for cowards, and only far right Republicans could be Christians. Then had the gall to say “Don’t get political.”

I would’ve preferred the American evangelical church had said nothing, or at the least, “Let’s respect all sides.” Literally anything else. As someone who works in a hospital and is also a POC, mostly I felt embarrassment. Pastors in 2020 lived outside of reality.

I was told, “Not all pastors, not all churches, leaders, bosses, men”—

But we already know that. I’m grateful for good churches, especially now. But consider even one wounded person is 100% harmed and it matters to them. To say “not all” is to say “not me” which does nothing for those already harmed.

I was told,

“Just trust God.”

But God is all I trusted, especially in this lonely season.

I was told,

“Don’t look to people, look to God.”

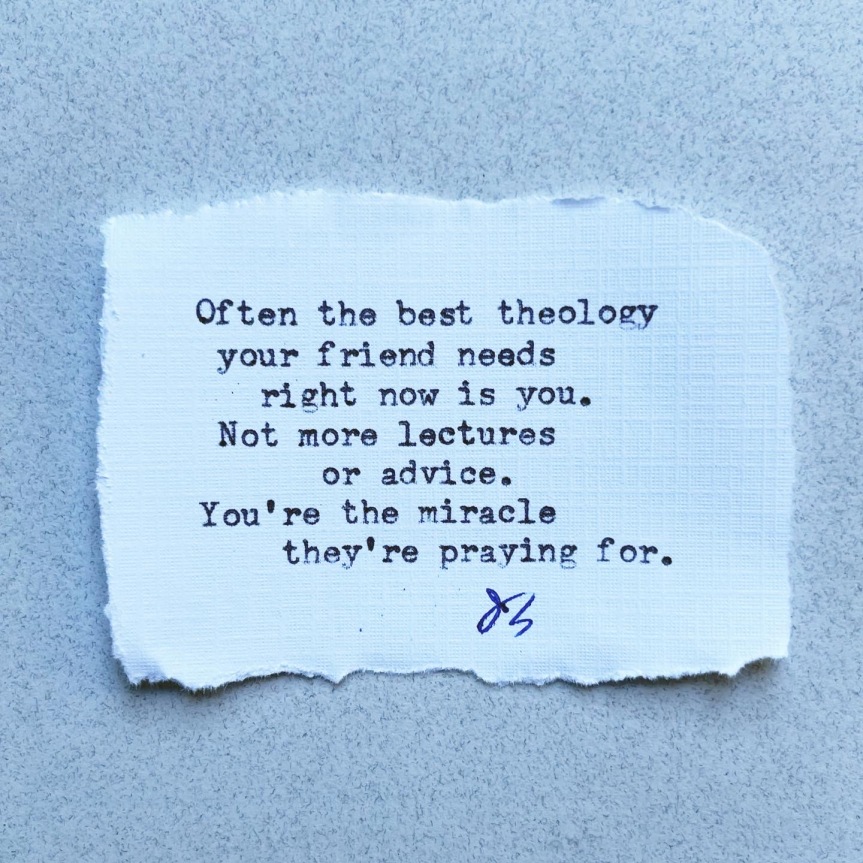

But this was a complete cop-out, and I saw where God was looking: to the people.

I was told,

“Stop badmouthing the church.”

But not keeping leaders accountable was literally badmouthing the victims, the church.

I am grateful to the remnant who cared for these wounded. For the healthcare workers, therapists, and clergy over the last twenty-one months who have put compassion over conspiracy. For me, the wound is still too deep. I grieve the vision of what I knew the church could be and hardly was. I grieve knowing maybe this was who many churches really were. I grieve the many leaders I admired who were fooled. I grieve my optimism and complicity.

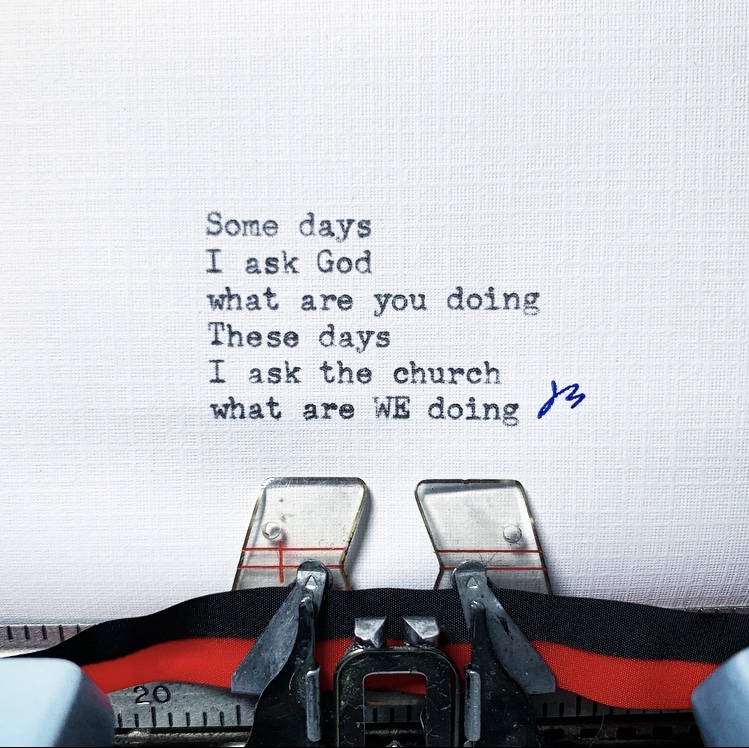

I’ll say it again. If your faith is making you a jerk, throw it out and start over. If Scripture is your guide, it must move us to justice, to be more kind. Otherwise it’s not what Jesus had in mind.

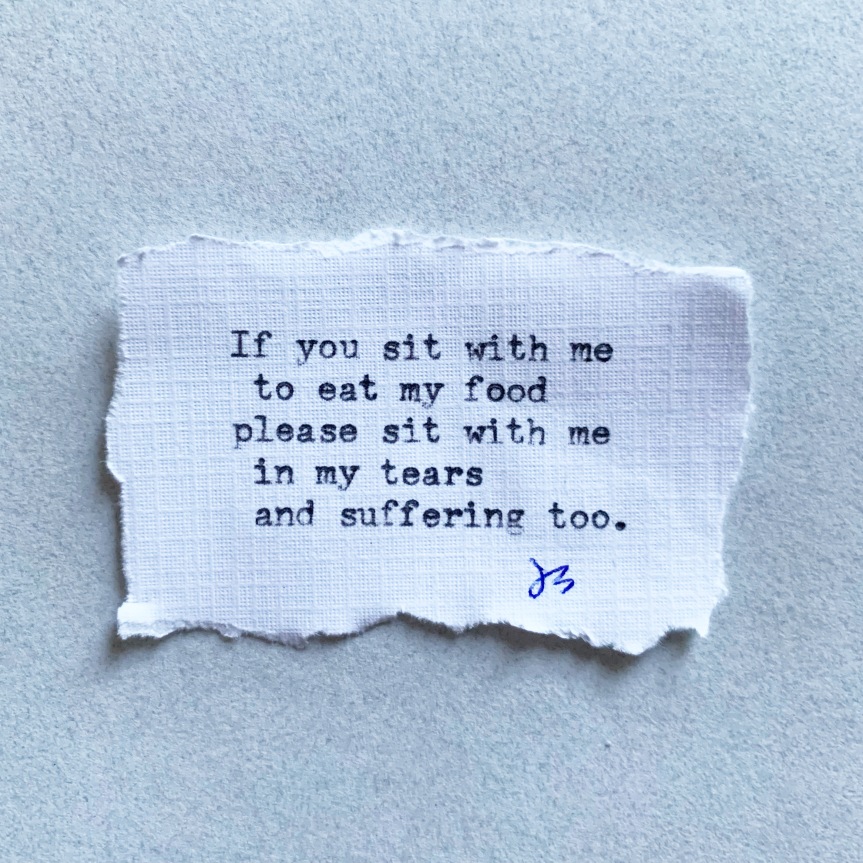

Over and over I heard stories of people wounded in church by abusers, predators, and political opportunists who worshiped a party over people. Pastors fired for not lifting up Trump. Victims who came forward to their pastors and were shut down or further abused. POC who needed hope and were told, “Calm down, God is in control, don’t worry about it, here’s a guest speaker who’s Black.”

I will never understand how Christian leaders are quicker to defend their denominations over the abused. The church isn’t some institutional concept that needs defending. The church is the people who needed our defense, the ones abused by leaders lording the institution.

When far right evangelicals throw insults because I talk about justice, masks, mental health, and fighting misogyny and racism, it is assumed I am “not in God’s Word.” I can assure you: the work of justice is straight outta the Word of God. Not a brag, but I’ve read the thing a lot. Six times now going on seven (not that the number matters; the words are there for anyone to read). Each time spoke differently. But on justice? That has always been the heart of God. Scripture, if anything, is the fuel for talking about these things. About the wounded.

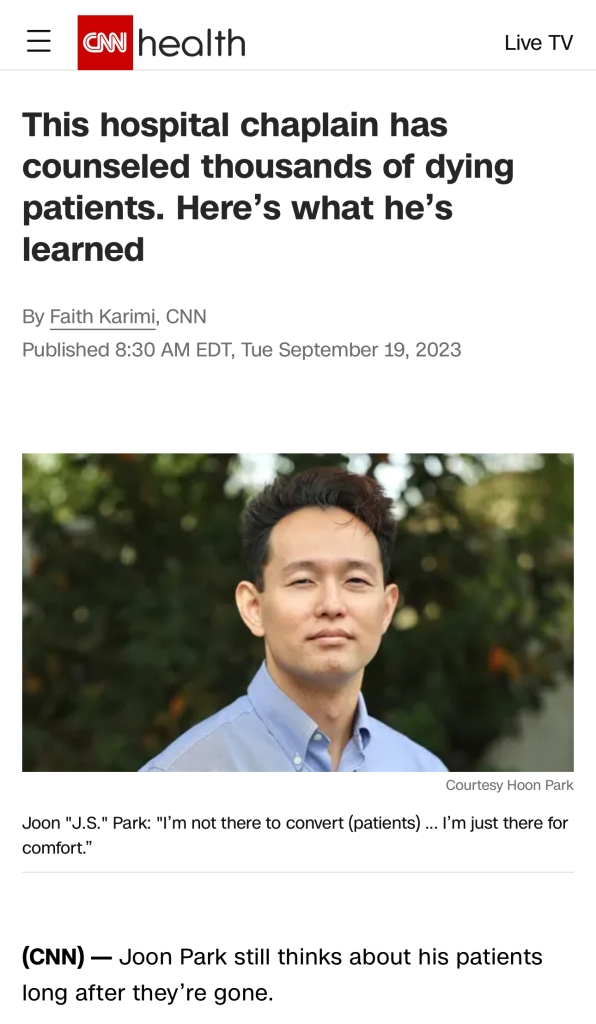

My faith has changed a lot over the years, especially after becoming a chaplain. I am a witness to suffering around the clock. One of the truths that remain: the Bible is precious to me, which is why people are precious to me. Scripture calls me to see fully. And I hate when it’s used to abuse. It is *for* the abused. Even in the worst of my doubt and disappointment, Scripture calls me to compassion. Never less.

— J.S.